Baja Banditos

In July of 1969, eight friends took off in two planes for a fishing trip at the very tip of Baja California. Our first fuel stop below the border was Serenidad Mulege. A strong north wind was blowing. Airports in Baja typically have humps and holes and hooks in them. Add nearby hills and you have Mulege. Over the plane-to-plane Unicom, I warned Jack, the pilot of the other plane, about a tricky feature of Mulege. It was his first cross-country flight after getting his license. "Hills at the south end of the runway form a natural 'venturi,'" said I into the microphone. "Which means exactly what?" Jack asked. "The wind accelerates through a passage between the hills. I plan a steep descent with only 20 degrees of flaps, nose high." "Not me," said Jack after a pause. "I'll go to full flaps, shallow descent, nose low." Now, I'll admit I do not know everything about flying. During the approach, I thought over Jack's method. Maybe nose low is a good idea. "Okay, Jack, I'll try it your way." The wind came whistling through the venturi. With full flaps and an extra ten knots it took plenty of power to hold a shallow approach. Suddenly the wind seemed to 'ungust' itself. Just before touchdown, we picked up more groundspeed than was appropriate for a short field. With our nose low, all three wheels hit at once, an undesirable situation for tricycle gear, especially on a sandy strip. Two-Four Fox commenced a loping oscillation. Brakes were only intermittently effective. The plane skidded the last few feet and came to a stop at the gas pit, a wide-eyed native just beyond our idling propeller. Fenton, my neighbor from across the street and front-seat passenger for the trip, asked if that was a typical landing. "Hardly," I said with forced nonchalance. "Mulege's runway is the best in Baja." Fenton was not amused. Neither were Sol and Al, my backseat passengers. Jack's plane, a Cessna 206, came into view out over the gulf. I reached back into the cockpit of Two-Four Fox for the microphone. "Jack, I probably didn't do it right," I said. "Just in case I did, though, you might want to reconsider that nose-low idea of yours." He had a worse time of it than I did. After galloping down the runway nearly digging in his prop, Jack went to full power and struggled off the ground for another try. About then, the wind subsided and Jack got his plane to stay on the ground, plowing the sand with his main-gear. Two of his passengers, Ted and Henry,

climbed out and ceremoniously kissed the ground. Sei,

ever inscrutable, made for the outhouse. Smoking his pipe at a nearby table, was a thoroughly weathered pilot named Fisk. Col. Fisk had more log books than both Jack and I had flying hours. He spends most of his time in Baja since retiring from the Air Force. My son and I met him on a previous trip. I suggested to Jack that we let the Colonel settle the matter. And to make it interesting, the loser should buy lunch. Jack agreed. The eight of us gathered around while Jack explained the situation to Col. Fisk. The question: Would you land with partial flaps nose high or with full flaps nose low? The Colonel puffed on his pipe and contemplated the matter carefully. A licensed pilot since the '40s, he had flown everything from crop dusters to B47s. We waited for his verdict. "Nose-high," said Col. Fisk. Winning is an infrequent event for me. I am not good at it. Jack apparently has not had much practice losing. While I chortled, Jack gnashed his teeth. "A deal's a deal," he said. "But I just have one question." Jack turned to Fisk. "Why?" Col. Fisk cupped his hand to one ear. Jack raised his voice. "Why would you land nose-high?" The old colonel sat back and crossed his legs. He smiled with every part of his face. "Simple," he said. "I have a little shimmy in my nosewheel." As we returned to the planes, Sol brought up the general problem of expenses for the fishing trip and got himself elected treasurer. I was named secretary; hence the letter set forth above. We continued south, flying the East Coast of Baja with the Gulf of California on our left. From here to Cabo, it is desert country. Ocean doesn't seem to belong. All afternoon my passengers and I were captivated by the unspoiled scene unrolling before us. The winds continued out of the north, so the flight to Rancho Buena Vista was going faster than originally planned. That should mean plenty of daylight for our landing. Still, the sun had already retired behind the hills when the two Bandito planes wheeled in the sky over Rancho Buena Vista. Eight flight-weary gringos sat down for a family style Mexican dinner. We divided into two-man fishing teams and retired early. The next day, each team set out in separate 18-foot boats. Fenton was my partner. "Donde esta los pescados?" Fenton learned to cry out, whenever it occurred to him. The skipper and his helper would smile at him then shrug at each other. Soon enough we each hooked a marlin. First Fenton, then me. The spectacle of the majestic fish leaping and plunging, the great force on the pole -- these experiences will stay in my memory. Something else, though: From the moment of hook-up, the marlin loses its stomach and is doomed. The tragic outcome is never in doubt. That evening, I told Fenton, I did not wanted to catch another marlin. Ever. "What'll we do for the next two days?" he asked. "Fenton, we shall

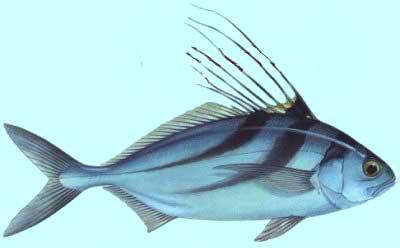

go for the toughest, most impudent fish in the sea --

the rooster fish." It was a decision, Fenton would

thank me for.

All through the next day, Fenton and I hunted and fought the bastard-of-the-sea. Once we had a double hook-up for a hundred minutes, with our respective foes collaborating against us to tangle our lines, forcing us to interchange chairs on the rolling deck. My rooster would come along side and give me the finger. Then he would think up something new and make a dash, heating up my reel against the friction. Until he runs out of ideas, you can never land a rooster. I nearly gave up, exhausted from laughing. The following morning, I took a plane-load to La Paz. The rooster fish is more than incidental to my story. Read on. Henry, the only unmarried Bandito, hadn't caught any fish and wanted to check out the senoritas. Fenton and I had already fought roosters, the ultimate in fishing. Ted, the only one to catch a sailfish, had enough of rocking boats. For me, any excuse to fly would do. We dropped Henry off with his luggage at La Paz, the only airport in Baja with a paved runway. Our return flight took us over the hills to the west coast, then swooping down to admire ranks of breakers that caress the beach below us and finally around the tip of the Forgotten Peninsula.

Upon landing, I

neglected to log our flying time and power settings.

On the return trip north, my oversight nearly cost me

an airplane, if not more.

By my reckoning, Two-Four Fox still had about an hour's worth of U.S. fuel in the right tank and two and a half hours of Baja fuel in the left as we said goodbye to Rancho Buena Vista the next morning. My plan was to make for Bahia de Los Angeles, non-stop. Non-stop, yes. The other plane departed ahead of us. Jack had to land at La Paz to pick up Henry and would rendezvous with us in the sky on the way north. Once aloft,

Fenton and I exulted about the rooster fish. "El

pescado con cojones!" Al and Sol snoozed.

Expecting headwinds, I set up our cruise, top-of-the-green

at 8,500 and unfolded my special Baja chart.

Jack called me after his take-off from La Paz. The 206 with its turbo-charger was already climbing through 6,000 for 12,500. I told him to ask Henry if he brought any souvenirs aboard. "You mean Lothario de La Paz? Don't want to wake him." Jack said that if we chipped in for Henry's lunch in Bay of L.A., we would hear the whole story. "The four of us are in," I said. I hung up the microphone and went to work checking ground speed. Sure enough, we have a headwind. Throughout the trip, I have gradually depleted my U.S. fuel in the right tank doing departures and approaches. Northbound, I have mostly Baja fuel, which I use only for cruising at altitude. I reclined my seat, adjusted the trim, and scanned the panel. Hey, the fuel gauge for the left tank reads less than a quarter. The needle swings down, sometimes reaching its bottom limit. Exactly how much Baja fuel do I have? I do not trust fuel gauges, of course, but I have never before seen the needle bang against the pin like that. I reviewed the entries on my knee-board. Suddenly I remembered the excursion to La Paz. "How long were we up yesterday, Fenton?" I hoped he wouldn't ask why I ask. "Why do you ask?" he asked. Fenton had a good view of the fuel gauges, which are on the passenger side of the panel. Guessing the answer to be an hour and a quarter, I re-calculated fuel-on-board. We were short by thirty minutes, the amount I had planned as a buffer. I felt a tap on my shoulder. It was Al. "When're we going to land?" he asked. "I gotta take a leak." "Figure an hour." Reducing the power setting would extend our time aloft but won't get us very far north against this headwind. Maybe Jack has made a wind-check. "What are you getting up there, Jack?" I asked over the radio. "Standby." To calculate my own wind measurement, I needed a checkpoint on the ground. I began looking out ahead for an island in the gulf that appears on the chart. I checked my chronometer -- where the hell is it? Something is not adding up. The shape of the coastline I see on the ground does not match the chart. "Twenty knots on my nose," said Jack. "What are you getting at eight five?" "Not that much, maybe twelve or -- shit!" Just then the engine starts to shut down. I think it unnecessary to reveal what part of my anatomy was affected. I switched the fuel selector to the right tank. The engine hesitated for a month or maybe just a week then resumed its normal sound. So much for the Baja fuel. I wrote down the time, although I had no idea what I would do with the information. "Two-Four Fox, how do you read me?" Jack asked. "Jack, we may have to put down early." "You're going to miss a good story." Looking at the scene below, I see a jagged shoreline and rocky bluffs, but nothing matches the chart in my lap. Where are all the airstrips? I flipped the chart over and back again. Something caught my eye. My course line on one side did not match the one on the other side. "Fenton, hold the control wheel a minute." With both hands free, I pulled apart my special Baja chart. The tape had stuck two of the fan-folded segments together. There! The shape of the shoreline below now exactly matches the part of the chart that was being concealed. So much for the good news. I now know where we are, which is one whole fan-fold farther from where I thought we were -- and needed to be. "It's going to be more than an hour, isn't it," Al sighed. He and Sol were both in the audience for the tape-unsticking scene. "Give Al a sick-sack," said I. Sol managed a chuckle. Al did not. Peril aloft is painless and the sense

of it must be derived from needles and noises. Call it

'denial,' but I have stopped looking at fuel gauges

for now and the engine is running smoothly. For now.

Last I looked, the needle on my right

fuel gauge was moving ineluctably toward the empty

mark. I had glimpsed the future. It was an

exceptionally compelling metaphor for the final years

of the Petroleum Age. "Jack, you busy?" "Go ahead, Two-Four Fox." "How about going down on the deck to take a wind measurement for me?" "Out of twelve point five for two thousand." "Thanks, Jack." In the back seat, I hear a commotion. Sol is laughing. Al is doing his business. Fenton stares at the fuel gauges. Time passes. Jack comes up on the Unicom. "Two-Four Fox, I have you in sight. We're at six, descending. When we get level at two, I'll put Sei to work with his abacus." There is a beach within gliding distance ahead. Waiting for Jack's report, I have time to review the emergency checklist. For engine-out landing, airspeed is most crucial. I ran my finger down the page. Fenton watched. The beach passed below our left wheel faring. Now a flat area ahead on the desert looks best. I caught a glimpse of Jack's plane, ahead of us and low. Jack came on the radio with cheerful news. "Our first try gives no wind at all down here." I handed the checklist to Fenton. "That settles it," I announced. Then with little regard for how it might be interpreted, I said, "We're going down." After letting down to a thousand feet over the water, I pulled the throttle back to 21 inches of mercury and the steepened the propeller pitch to 2,200 RPM, endurance settings. The cabin became quiet. Airspeed has slowed to 110 knots now, but the rugged, possibly beautiful shoreline of Baja appears to pass by more swiftly. At the lower elevation, our gliding options are fewer, decisions have to be quicker. We wait. In twenty turns of the sweeping hand, Bay of L.A. will -- must! -- come within range. Meanwhile, an abandoned dirt strip has appeared below us. A precautionary landing there -- with power -- has to be considered. Think. Deep breath. Decide. My mind has become strangely viscous. Look down -- no, back. Too late. The strip is out of sight now. No decision to make. One last glance: Empty. I picked up the microphone and steadied it against my chin for a long minute. "Bay of L.A. Traffic, Two-Four Fox, five miles south -- uh, planning a straight-in." Jack, turning base leg ahead, called and confirmed no wind on the ground. "See you at lunch," he said. "Keep your nose high." Closing the throttle a mile away, I glided Two-Four Fox onto the strip and rolled off to the side. I looked over at a grinning Fenton. I pushed in the throttle to taxi. The engine coughed and died. The four of us got out and pushed Two-Four Fox to the gas pit. Jack and his passengers applauded. Our host, Papa Diaz, wheeled out a gasoline drum. I requested 20 gallons of Baja fuel for each tank. That fan-fold chart? I still have it

somewhere.

|

Light planes

come and go. Nobody even looks up. A Jeep beats its

way into a village along a dusty trail and the whole

town turns out.

Light planes

come and go. Nobody even looks up. A Jeep beats its

way into a village along a dusty trail and the whole

town turns out.  Experience is

what makes the rooster the quintessential

fighter. That plus resourcefulness and

initiative. He owns all the attributes you

value in a colleague and respect in a rival.

With affection, you shout at him, "You son

of a bitch!"

Experience is

what makes the rooster the quintessential

fighter. That plus resourcefulness and

initiative. He owns all the attributes you

value in a colleague and respect in a rival.

With affection, you shout at him, "You son

of a bitch!"

Probable

cause

was water in his fuel. Wynn tried to buy as

little gasoline as possible south of the

border. He brought his own chamois for

straining the stuff. Despite these measures,

Wynn's Pacer got converted into wheelbarrows

and cattle feeders for the local residents

of Baja.

Probable

cause

was water in his fuel. Wynn tried to buy as

little gasoline as possible south of the

border. He brought his own chamois for

straining the stuff. Despite these measures,

Wynn's Pacer got converted into wheelbarrows

and cattle feeders for the local residents

of Baja.  Aeronautical

charts are aligned with meridians, north and

south. Baja is on the slaunch. That

means pieces of Baja are published on eight

different documents. The rest of those

charts show nothing but ocean on either

side.

Aeronautical

charts are aligned with meridians, north and

south. Baja is on the slaunch. That

means pieces of Baja are published on eight

different documents. The rest of those

charts show nothing but ocean on either

side.