Ed, the youngest member of the team, is well into his sixties. He taps the spark advance just so. The engine rattles its mounts, half a hundred horses inside, oil-soaked and stomping at the gate, shirking their bridles. I can feel their hot breath. So can Luke. His job is the cooling system, a maze of leaky hoses. Once ruddy and freckled, now beyond senior years, "Cool Hand Luke" toggles his petcock and grins at me. We already laughed about that. Rusty water dribbles onto the concrete floor. Old Man Neilsen, the team leader,

reclines in his director's

chair in front of the dynamometer waiting for a signal

from Ed. The fourth

member of the team is Homer, a rough-hewn octogenarian

with silver tufts

for sideburns. He squats before the driveshaft,

tachometer in hand.

Taking unsteady aim with a screwdriver, Ed trims the butterfly valve. The change in mixture brings on a clamoring stampede, the steady pounding of mechanical hooves. Time for me to climb onto the footstool. The fuel level moves down the glass toward the first mark. I'm poised to punch my stopwatch. This first experiment at partial

throttle will take about

a dozen minutes. Longer, we hope. The way I have it

figured, 12 minutes

to burn two quarts means a certifiable breakthrough --

an encyclopedic

event!

Incessant vibrations tickle my ankles

and knees. Within

the engine, 50 horses are at full gallop. For several

minutes I let my

eyes take in the Bourke Engine and its dedicated

research team.

Ed braces his knee against the test-stand and tweaks the mixture. His coveralls were once either blue or gray. Homer's tachometer, which looks much like an oversized pocketwatch, is pressed against the driveshaft. He is bowed over its face, sweat streaming from his own. The flywheel fans the smoky air inches beyond his knuckles. Homer is wearing a lab coat. I wonder if that's for my benefit.

Homer led me into what was once a garage. "Neighbors complain if we fire up the engine much before noon," said he. Homer gestured with his thumb. "Meet Ed." "Hi, Ed." I took a quadrilled pad out of my briefcase and followed Homer along a row of machines: lathe, mill, precision grinder -- a toolmaker's dream shop. "That old fogey is Cool Hand Luke over there with his water hoses. Come shake hands with this guy, Luke." A bald, bespectacled fellow greeted me with a smile." And here's the boss," continued Homer. "We call him Old Man Neilsen. Luke calls him something else." "Only when I'm not around." Old Man Neilsen stood up from his director's chair, arms akimbo. He studied me warily through drugstore spectacles. A lifetime of calluses gripped my hand. The boss was ordinary in stature and paunch, unremarkable in every way -- except for his garments: golf cap worn backwards, dress shirt tucked into Bermuda shorts, dark socks and sandals. He exchanged glances with the others one by one. Each nodded solemnly. I was OK.

"Mr. Neilsen, to what do you attribute the high efficiency?" "Runs smooth," he shrugged. "Getting rid of vibration is the whole idea. That way you turn high RPMs, get more pick-up." Homer explained that Bourke died in 1968, leaving the engine to his friend Neilsen, who promised to continue its development. He and his chums retired and moved with their wives to Nevada. The three of them all lived in the same neighborhood in North Las Vegas. They worked on the Bourke Engine during the week then ran horsepower experiments on Sundays. "While our wives are in church," said Homer. "We needed a machinist that would work cheap. We found Ed here. This young fella was souping up drag boats on Lake Mead. Gave him a few beers and he rebuilt the combustion chambers." "Ordinary connecting-rods are all wrong," Luke volunteered. He was the only member of the team who permitted his face to smile. "Rods flap back and forth, side-to-side." He pointed a greasy finger at Figure 1 in the patent. "The Scotch Yoke here gives you a nice even piston motion." Homer raised his silvery eyebrows. "Sinusoidal," said he. I put the notebook back on the bench. "You will excuse me for saying so, but whatever you do in the crankcase simply cannot have much effect on fuel economy." Homer's jaw jutted. "You ain't seen the data!" Old Man Neilsen, held up his hand. "I don't mind telling you, nobody was more surprised about getting three-point-three than Russell Bourke himself." "But Mr. Neilsen," I said, "there are a lot of dreamers out there. Imagine how many of them show up on the doorstep of GM and Ford -- especially right now, with everyone talking about gas mileage. My recommendation of your technology is predicated on confirming the measurements." "Data speaks for itself," said Homer. Whether he knew it or not, Homer had proclaimed the most fundamental principle in science.

Coming up on 12 minutes. Anything beyond that time will confirm the Bourke Engine's place in history: Three-point-three horsepower-per-goddam-pound-per-hour! Now I see it. Something is wrong:

The pulleys!

"Shut it down!" I hollered. My first reaction was to terminate the experiment, as if there were some kind of an emergency taking place instead of merely a reality attack. Ed stopped his tweaking of the carburetor and cupped his hand behind his ear. No doubt whatsoever: Experimental error has been caught. Reality prevails. I wanted to climb down from the footstool and explain. Homer freed one hand from his tachometer and waved insistently. He pointed at the fuel bottle. I glanced up and saw that the level had passed the bottom mark. I felt my thumb click the button on the stopwatch. Ed closed the throttle. Old Man Neilsen released the brake. Suddenly silence. I removed the cotton from my ears. Homer was first to speak. "What did you get?" "Twelve minutes. However -- " "Twelve minutes and what, for crying out loud!" "A little over 24 seconds, but I gotta say something, here." Luke beamed. "Best we ever done." He clapped Old Man Neilsen on the shoulder. Ed tossed his screwdriver in the air and gave out a cheer. "Slipper-yoke! That new shape slams them fuel charges real good." Old Man Neilsen, face crimson, opened the refrigerator in the corner of the shop. He offered me the first beer. Homer cocked his head toward me. "What you got to say now?" I shook my head. "It's the pulleys." Luke and Ed linked arms and danced a jig, kicking water on Homer's lab coat. Old Man Neilsen lifted his beer to salute the Bourke Engine. Homer popped a can-top. "Figured you'd see them pulleys." "You know then!" I exclaimed, utterly astonished. "Sure," said Homer, after taking a long swig. "Only makes our data better." "How do you figure that?" "The friction -- that's what you're worried about -- friction from the belt scrubbing those pulleys. Belt drag. Hell, that only means a little horsepower lost on the way from the engine to the dynamometer. We figured that out more'n twenty years ago, didn't we, Luke?" Luke put down his beer. He was not smiling. "No," I said. "That's not the problem. Look here, the pulley on the brake is bigger than the one on the engine." "Horsepower don't care about pulleys," Homer snorted, holding up his tachometer. "Only RPMs." Old Man Neilsen strolled to the

workbench and flipped

through the pages of a dilapidated shop manual. He

handed it to me. A smudged

page told how to calculate horsepower.

A moment of pondering, and I might have kept the matter to myself. But no. Dreams be damned. My ego and I, flushed with victory over error, indulged a primitive reflex: to disabuse these guys of their misconception. Luke had backed up against the far wall, face ashen. He caught my eye and shook his head slowly. I watched him cross his lips with his index finger. "The RPMs," I blurted, "have to be measured on the same shaft as the torque." I reached for the yardstick. Then, having finally caught Luke's drift, I drew back. Cool Hand Luke nodded his appreciation, but it was too late. "Pulleys don't mean nothin'!" protested Homer. "Luke, tell 'im. This son of a bitch got no business coming in here mouthin' off about pulleys." Luke made no reply. Suddenly I didn't want to be right. It was for a time like this that the word 'shit' was invented. I studied the tops of my shoes. Luke mopped his brow with a shop rag. His eyes were glistening. For a long minute, the only sound was the clicking of the Bourke Engine cooling down.

Old Man Neilsen, face drawn, leafed absently through the notebook. "I was afraid this would happen." "So we're not exactly getting three-point-three," Homer said. "Can't we just use a correction factor?" "I was afraid this would happen," repeated Old Man Neilsen. "The horsepower isn't what we thought." "Our data is off by one-third is all!" Homer protested. "Two-point-two, then. That's what we're gettin'. Nobody else ever did any better than two-point-zero!" Ed checked the pulleys again. "The engine," he said, "is delivering only one-third as much as -- " "Which means exactly what!" "Homer, it means we're gettin' less than twenty horsepower." Old Man Neilsen shook his head. "All those damned years! Why didn't we ever think about the pulleys?" Cool Hand Luke folded his arms. I watched a grim smile tremble across his face. He knew about the pulleys -- for decades. For hundreds of Sundays, Cool Hand Luke showed up to monitor his gauges and toggle his petcock, to nourish old men's dreams. Greater love hath no man than this, that he should lay down his reality for his friends. Charity work, Luke might have told himself. Not much good at golf anyway. Homer took a shuddering breath. "Ed, that damned thing's running at only one-point-one!"

Specific Fuel Consumption: The expression "specific horspower" (hp/lb/hr) has been adopted for the general audience in place of "specific fuel consumption" (lb/hp-hr), which is the more common technical phraseology, inasmuch as "specific fuel consumption" has been appropriated in recent times to characterize fuel economy of motor vehicles (variously gm/mi, gal/ton-mile, kg/tonne-kilometre). Typical specific fuel consumptions run about 0.5 lb/hp-hr for gasoline engines and 0.4 lb/hp-hr for Diesels.

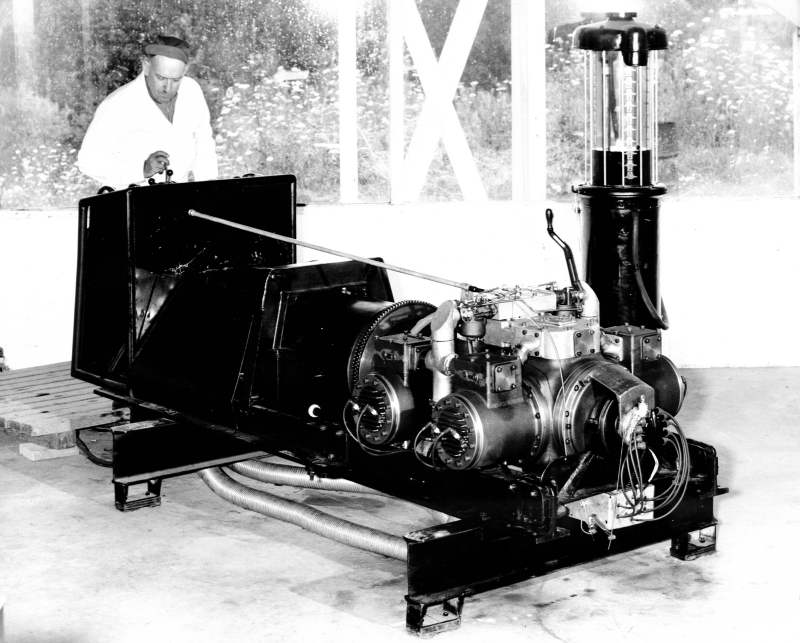

Russell Bourke and the 400-Cubic-Inch Engine: The patents ran out in 1957 (photograph courtesy of Roger Richard). |

Luke

lifted a tarp. The Bourke Engine, too, was

undistinguished -- from the

outside. The machine quite plainly boasted four

cylinders, horizontally

opposed, the same size and form factor as a VW engine.

Homer opened a notebook

full of hand-ruled data sheets and a yellowing copy of

the Bourke patent,

which had expired a dozen years earlier. I cleared my

throat.

Luke

lifted a tarp. The Bourke Engine, too, was

undistinguished -- from the

outside. The machine quite plainly boasted four

cylinders, horizontally

opposed, the same size and form factor as a VW engine.

Homer opened a notebook

full of hand-ruled data sheets and a yellowing copy of

the Bourke patent,

which had expired a dozen years earlier. I cleared my

throat.