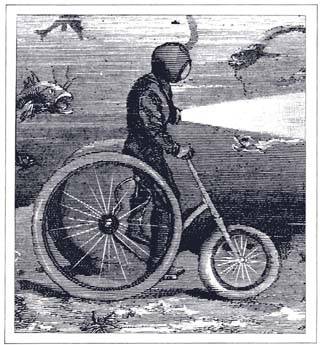

The twentieth century will be remembered for achievements in "the new ethology." Under one discipline called "sociobiology," discoveries in widely disparate sciences are being drawn into confluence -- behavior and statistical analysis, genetics and ecology, game theory and biochemistry. Some of evolution's most vexing behavioral puzzles may soon be solved Altruism, for example. What possible "fitness value" can be derived from a self-sacrificing behavior? Inter-species cooperation is another example. Many of nature's most successful creatures exhibit cooperative behaviors in varying degrees. But why? Sociobiology teaches that the behavior of a living thing -- as well as its structure -- is determined to a large extent by information carried in the genetic code. Thus, the adult weaver bird, nurtured in isolation, nevertheless crafts an intricate nest when given access to the requisite materials. Nature, according to the new ethology, selects those variations in behavior which show the greatest success in perpetuating the genes. Not necessarily the individual, mind you, but its genes Animals have come to be regarded by sociobiologists as hulking contraptions programmed to serve the long-term survival interests of infinitesimal specks of DNA that slosh around within the nucleus of every cell. An illustration may clarify the concept. Take the case of the mutant human strain, bicyclius sapiens, which began to re-appear near the end of the petroleum age. Previously, its new-world habitat was overrun by the swifter auto-patheticus. The non-aggressive behavior of the bicyclius was no match for the patheticus, the latter gaining territorial advantage through a genetically programmed expedient: petroleum plunder. Certain anatomical defects in auto-patheticus, such as anterior obesity, were thus shielded from environmental stress. The bicyclius mutation with its gentler, more cooperative tendencies didn't have a chance, seemingly, and the old Darwinian paradigms could not adequately explain their survival. But by yielding territory to the autos rather than competing directly with them, the bicyclius secured a precarious niche, wherein they could continue to eschew reliance on the combustion of fossils, expending bodily effort instead. Their genes carried into succeeding generations this peculiar behavior and, as it turned out, its adaptive advantage. With the rapid decline of economical supplies of their requisite resource, the auto-patheticus was left defenseless. A rapid shift in the gene pool was inevitable as the auto-patheticus, under severe selective pressure, failed to produce survivable offspring. The bicyclius sapiens was then found

to be well suited for the conditions prevailing in the post-petroleum age

and succeeded in reclaiming its primacy.

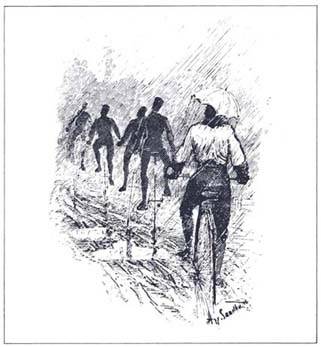

Women suffer more in the cold than men do. Unfair as that may seem, it's a fact. Start with the notion that behavior in animals is influenced to varying degrees by coded chemical messages originating in the genes. Variations do arise, of course, otherwise there would be no evolution and we'd all behave like amoebas or something. Variations in behavior which afford the greatest "fitness" are most likely to prevail into succeeding generations. Survival of an individual doesn't necessarily assure the perpetuation of the genes that encode a particular trait. Offspring carrying those genes must be produced. But even that isn't always enough. The offspring have to be nurtured until they can produce offspring. In some species, that's quite a project. In the human beings, it takes years to raise reproductively competent sons and daughters.

Millions of years ago, a variation in mammalian behavior appeared which assigned most of the nurturing of mammalian infants to mothers. This seemingly arbitrary practice must have worked. It was firmly established by the time the human species appeared. One of the first threats to the infant is thermodynamics. The newborn is so small that its surface-to-mass ratio is dangerously high. That makes it vulnerable to heat loss. Protection of the offspring from cold is one of the highest parental priorities. Let's suppose that early in human development, a peculiar variation came along. Adult individuals were characterized by an acute sensitivity to cold. In males, this attribute was undoubtedly a handicap -- in winter hunting, for example. Maybe not in females, though. Pre-ancient women probably did more than complain about drafts. They wrapped up well to keep warm. If they happened to be doing some nurturing when a chill struck, those early mothers provided needed warmth to their infants as well -- a biological early warning system. For the newborn, it might have been a life-or-death proposition. Under our supposition, this behavioral variation would have conferred some fitness value to the offspring and thus to the parent's genes. Assuming, then, that the female's cold-sensitivity breeds true, the selective advantage would favor those genes and, over successive generations, they would become abundant in the gene pool -- down to this very day. Cultural changes, such as those brought about by the women's liberation movement, can abolish economic and political inequities rather quickly. Biological evolution -- even with harsh environmental pressures -- takes generations to accomplish even minor reformations. A number of biology's sexual asymmetries, including women's extra sensitivity to cold, unfair as it seems, will naturally persist. That's probably why a few women are reluctant to ride their bicycles in winter. On the other hand. it doesn't seem to stop many others from enjoying skiing. Codes for some behaviors, as well as for structures, are still carried deep inside our chromosomes, whether we like to admit it or not. Are we not survival machines, programmed for the perpetuation of the genes that produced us? To some people, human behavior is too complex tor genetic explanations. They prefer to think that our behaviors are almost completely under voluntary control, that we are more strongly influenced by what we have learned during our own life-times than what our genes have "learned" over the eons -- and that the content of what we learn is dominated by something called "culture." But then where did culture come from? Did it, too, evolve? And what fitness criteria govern that process? Wouldn't cultural selection run parallel to natural selection? As for behavioral complexity, consider digestion. Pretty complex and culture has little to do with it. Also, let's not forget how honey is made and, oh yes, the weaver bird's nest. Culture may serve primarily as a proximate, intermediate link in a chain of explanations for human behavior. Ultimate causes will often be found deeper in our biological heritage. Not always, though. Whereas flight has evolved independently at least four times in nature, bicycling had to wait for the evolution of human beings. And their cultures. |

|

|

|

|